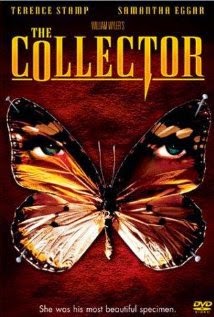

Rated: UR

Run Time: 119 mins

Director: William Wyler

Starring: Terence Stamp, Samantha

Eggar, Mona Washbourne

The Collector’s Freddie Clegg is an altogether

different sort of villain. He is, in some ways, more sinister than most. With his bland cunning

and dough-faced innocent visage, he is almost sympathetic. As such, he is

much of a kind with a new sort of killer that had ostensibly arrived with

Hitchcock’s Psycho and Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom of the same year, 1960. I

suppose one could make an argument that the character had appeared much

earlier still, with Peter Lorre’s child killer in Fritz Lang’s M or even Hitchcock’s own particular

version of The Lodger.

This new type of killer was the

kind of fellow who could not have a real relationship with a woman unless it

were characterized by possession and dominance. Movies of this ilk were

prototypes for the European (and I say European for a reason, because I am not

entirely convinced the Italians created the giallo) giallo. Later, the

giallo as a sort of prototype would be replaced by the dreaded slasher

flick. These newer films featured an antihero who was not as much

“psychologically motivated” as straight-out motherfucking batshit crazy.

Superficially these men are outwardly normal, if eccentric, but they are always

incredibly introverted and pathologically shy. This was the first (or,

second if you must have it that way) incarnation of the psycho killer. He

is with us still, to this very day.

Our first sight of Freddie is as

he lopes at a slow jog through a field, chasing a butterfly. It is a rare

specimen apparently, and will be a welcome addition to his vast collection (this

is a motif that would be used again by Thomas Harris many years later in The Silence of the Lambs,

although the metaphor would be reworked). Near his jaunt, there is a

large manor house that is for sale. There is an attachment to the

structure that is composed of an outer room and, down a series of steps, what

can only be described as a dungeon room with sinister stone walls. This

gives Freddie an idea. It’s an idea that’s been forming for some time,

actually. He has recently won a large sum in what seems like a lottery of

sorts (they call it the football pools), and, as this idea is going to cost a

pound or two, his recent winnings are fortuitous indeed.

Now, it is certain that Freddie

is not going to miss his job very much. His co-workers mock him.

It’s easy to make fun of the outsider, the alienated, and the lonely.

Cruel people do it. I am convinced that the ones who embarrassed or

humiliated you in school never really change, unless for the worse. I

pity poor Freddie his social awkwardness, his inability to transcend class and

his lack of culture (this is one of the purported reasons John Fowles wrote the

book, to out and condemn the ugliness of class conscious England in the era of

the “angry young man”). What is a poor whacked out psycho freak bug

collector with a vivid fantasy life to do? Eventually, Freddie buys the

house and retires to live the life of a country squire.

Oh, and he kidnaps a girl he’s

been ogling from afar to put her up in that dungeon I just mentioned.

This is the plan that Freddie, like any good incipient serial murderer, has

carefully nurtured, for which he has plotted the logistical details for some

time. Like anybody who means business, he has not only thought a great

deal about it, he’s got a by-God plan.

As if she were a butterfly, Freddie uses chloroform to anesthetize a young art

student named Miranda Grey, to whom he’s taken a fancy. He then books her

a room at his “wow, am I whacked out crazy or what?”

B&B in the country. He has done this in the unspoken hope that she

will “learn to love him.” He lays her out in a bed, takes off her shoes,

and the chastely pulls down her skirt (which has hitched up). From these

very first gestures, we can see that Freddie objectifies Miranda much as he

does his extensive and marvelous collection of butterflies.

Sound familiar? Well,

that’s how John Fowles wrote it, and he absolutely deserves the credit for this

archetype (unless Robert Bloch does, it’s a close call; the taxidermied birds

of Norman do precede Freddie’s flittering

butterflies). The lonely, introverted, keeps-to-himself, “he was always

such a quiet neighbor” type of perverted psycho creepoid (think Ed Gein, Reg

Christie, Dennis Nilsen, Jeffrey Dahmer). The sort of man whose only

means of experiencing a relationship is through the twin lens of obsession and

ownership. A fellow who can only feel passion through a prism of

voyeuristic objectification, possession.

The scene after his plan goes off

(flawlessly) is interesting. He secretes her in the room he’s laid out

and goes into the main house. Then it starts to rain. While he

first narrowly escaped becoming drenched with the initial downpour, he now

willfully runs into the deluge with a childlike joy that reads like a release

of tension, a relaxation and self-satisfaction with his success. This is

juxtaposed with Miranda awakening in gradually dawning horror at her

predicament, before Freddie descends the steps and she sees him for the first

time.

Stamp and Samantha Eggar as

Miranda breathe life into their literary counterparts, only two years

after the novel was written (Fowles wrote the screenplay himself). I

don’t know if The Collector is a classic of literature (perhaps a

minor one?), but there was very little time left to the prospective filmmaker

to gain any perspective on its importance as a work or for the literary critics

to tease out possible meanings before it was committed to film. Yet,

Fowles was apparently happy with the finished product. That is largely because

of the leads, I think.

Terence Stamp plays to the

nuances of the character marvelously. We know Freddie’s up to no good

from the start, but it is only as the action progresses that we begin to

understand just how bad he really is, how dangerous. Every

escape attempt Miranda makes is quickly revealed to be a trap laid by Freddie

to test her, whether or not she’ll really stick around, whether she really

likes him. How much can you trust someone you’ve kidnapped and

sequestered in what amounts to a medieval dungeon that you’ve creepily

furnished as a young lady’s boudoir?

Samantha Eggar as Miranda is, I

think, ultimately whom we pull for, not Freddie, whom we may pity but who also

revolts us. As a character, she is alive with the potentiality of youth,

energetic, clever, and desperate. It seems such a simple thing to create

characters who represent microcosmic types but who are also recognizably human,

but I suspect it's not. Their performances and their chemistry

keep our interest in a movie peopled by so few

characters.

In praising the acting, I'm not

neglecting the direction of the great William Wyler. If I remember

correctly, it was he who gave such sage practical advice on film acting to,

yes, Laurence Olivier (in Wuthering

Heights). Wyler turned down the opportunity to direct The Sound of Music for this movie

(Robert Wise, of The Haunting, took

the reins; it’s a small world), a wise choice if you were to ask me. One

is considered a classic and the other is little known now, but I still prefer

the thriller to the other.

As an aside…man, directors in the

old days were versatile; check out Wise’s CV some time: psychological horror,

Val Lewton RKO B-Unit horror!, musicals, science fiction, noir thrillers,

adventure, westerns, war films, mysteries...incredible, and many of them

classics.

Fowles later wrote that the book

was in part a diatribe against class conflict and how that conflict manifested

itself among the ineffectual efforts of the working class to ascend to the

station of their betters and the inability of the snotty privileged classes to

understand what great responsibility their good fortune placed on them.

In this context, the discussion of The

Catcher in the Rye is

enlightening. I’ve read Salinger's book and been conditioned, as has

Miranda, to regard it as a modern classic. But I cannot find fault with

Freddie’s dissection of it. His argument that the literary criticism that

has lionized Salinger’s best-known work it is all so much pseudo-intellectual

posturing is not unreasonable.

But when you make your hoi polloi

pseudo-antagonist a man who is incapable of empathy and your victim a female

who is a bit snotty and entitled, well-heeled, pursuing a liberal arts

education that we all know is a luxury of the privileged when the rest of us

have to get real jobs, well then you’ve rendered your tale with a bit of a

misogynist sheen. The movie cannot entirely escape that reading, either.

Still, while we can view Freddie

and Miranda as symbols of their social class, I would prefer a literal

reading. The characters work well enough as individuals. And I see

the film as being important more for helping establish a very interesting

horror stereotype that would be mined to great effect in the future than for

contributing anything of value to England’s discussion on class

distinctions. Who really gives a shit in the 21st century? Not an American, I can

tell you that. The movie still entertains because I believe there really

do exist people like Freddie Clegg, and they really are dangerous. And

we, although largely women it would seem, are their prey.

Freddie Clegg is deservedly

Stamp’s breakout role. Smallish, he never really seems too overtly

threatening, but his actions, and the clinical calculation that precedes them,

unveil before us, under out greater comprehension, a monster. The actor

is a slight guy, not much bigger than Samantha Eggar, but he is constantly

foiling her every effort to gain any slight advantage in their

relationship. It is as if he were cruelly toying with her as much as testing

her obedience. The way he does so creates an aura of

disquieting menace about the character. I can’t describe it better than

that. You'll have to watch it to see if you agree.

The movie is not without its

flaws. Perhaps the most egregious is that the screenplay doesn’t always

let the camera do its job. Show, don’t tell…good advice. The shot

of Samantha Eggar’s face framed, as a reflection, within the confines of one of

Freddie’s glass cases, full of mounted specimens, is a clever visual

metaphor. I don’t know whether or not the idea is, cinematically, innovative

as an image, but I at least found it satisfying.

Here's the problem, though:

the moment is ruined in the very next instant when Miranda just comes right out

and reiterates what we’ve just seen. We get it. She’s a new

addition to his collection. And he’s a collector. And the name of

the movie is, The Collector, which

is also, you know, the name of the book, The

Collector. I don’t know if this scene is in the source novel, but

that doesn’t make it any more palatable in the movie.

I want to revisit something I

wrote earlier. So very much has been made about the fictional

counterparts to Ed Gein over the years, but I wonder if, in The Silence of the Lambs,

Thomas Harris consciously chose to reuse the entomology angle from The Collector. Jame

Gumb’s interest in entomology is dissimilar to Freddie’s (and to Conan Doyle’s

villainous Arthur Stapleton, as well). Not that that book is concerned

with metamorphosis, any more than Psycho is concerned with naturalism.

But the use of entomology, specifically butterfly collection, as a metaphor for

obsession and the sublimation of sadism and homicidal misogyny in favor of a

more palatable form of possession (real intimacy, much less a normal and

healthy sexuality, is out the window for these men…like way-ass out the window) is a cogent

idea. Perhaps Wyler did not capitalize as effectively as he could have on

the visual possibilities inherent in the metaphor. The idea was right

there, presumably sufficiently elucidated by John Fowles. If so, it was a

missed opportunity.

There is not much else to say

about the movie, really. It’s just one series of narrow non-escapes after

another, the two of them bargaining for freedom and companionship in turn,

conversations about ideas, art, standards of beauty…and then it ends, just as

you think it’s going to end. And if you thought it was going to end in

any other way, you have not been paying attention.

The Horror Inkwell Rating: 5/5